Call for Ideas, Images and Maps: Counterpoints, A Bay Area Atlas by the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP) invites scholars, activists, policy analysts, artists, and organizers whose substantive focus is on the Bay Area -- either historical or contemporary -- to contribute to a collaborative atlas visualizing and exploring the causes, dynamics, and consequences of displacement in the Bay Area.

We also invite folks to donate to our GoFundMe campaign so that we can finance this project!

Contributors interested in expanding the public impact of their work are invited to consider how their research speaks to the ongoing housing crisis in the Bay Area and submit a proposal (<500 word) describing

(a) the data and/or narrative they would like to contribute,

(b) how their submission contributes to understanding and/or resisting the forces behind displacement in the Bay Area today, and

(c) how their submission fits into one or more of the themes listed below.

You may also simply submit a map, image or data visualization that you feel communicates something powerful about one of the below themes.

We are happy to consider visual work that has already appeared in other publications, assuming permission can be granted. Similarly, if you have amateur cartographic or GIS work that you feel communicates something important but is not quite professional in quality, don’t hesitate to submit. The AEMP will work closely with researchers throughout the editorial process to help visualize or revisualize data (e.g. stylize cartographic data, illustrate narrative data) and integrate contributors voices into the final atlas in the form of self-attributed, written contributions of approximately 1000 words each.

The AEMP is particularly interested in submissions that explore the themes of: colonialism and indigenous resistance; evictions; migration/relocation; public health, public housing, and environmental racism; land speculation; the gentrification-to-prison pipeline; and transportation infrastructure and economy. Please see below or more information on each of these themes.

We are also particularly interested in work that incorporates the full Bay Area, or those parts of the Bay Area not commonly discussed or studied, including parts of Northern California impacted by the region’s transformation which may not be part of the formal 9-county region.

Please submit all proposals to antievictionmap@riseup.net by March 4, 2018.

Themes

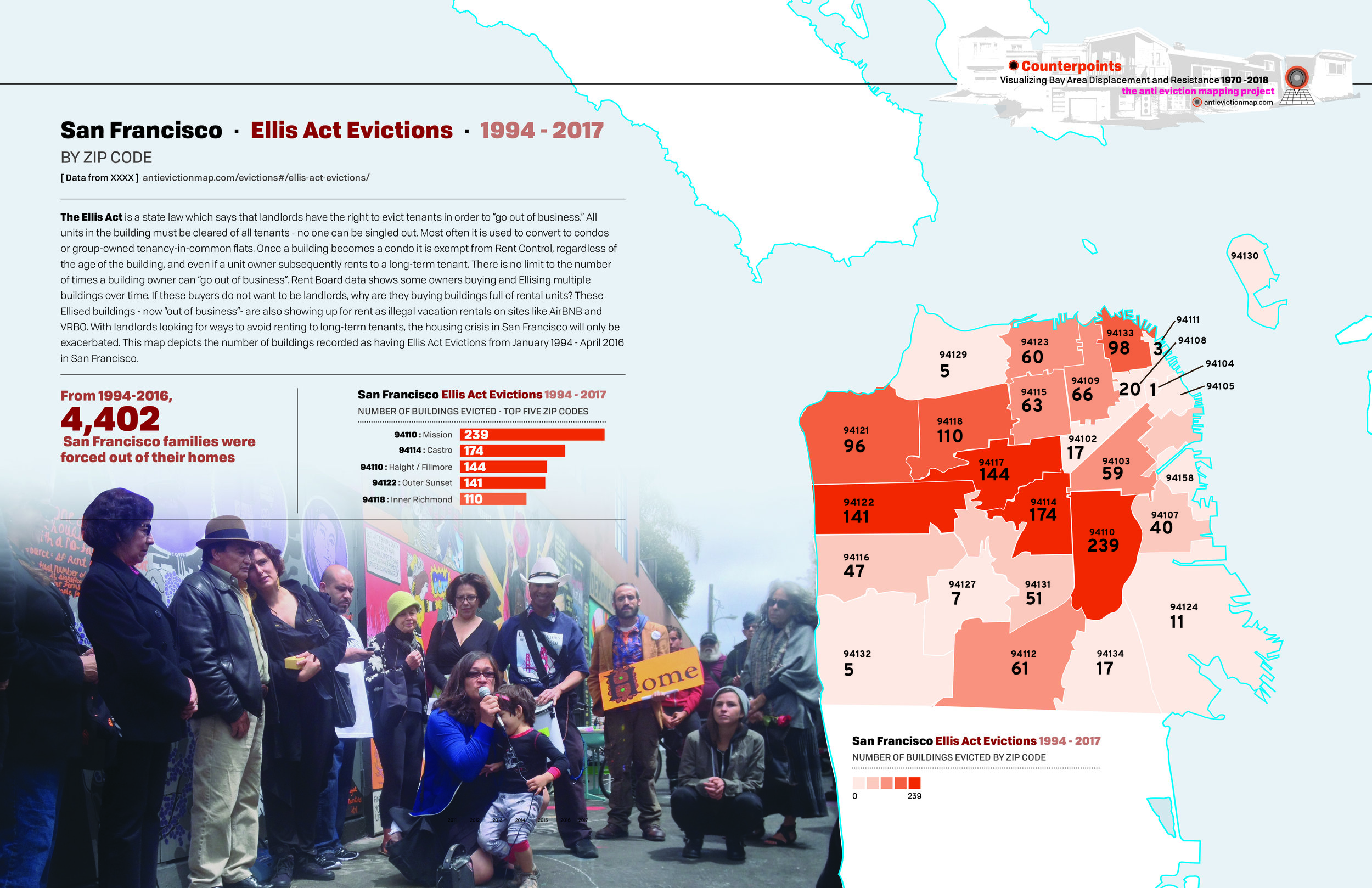

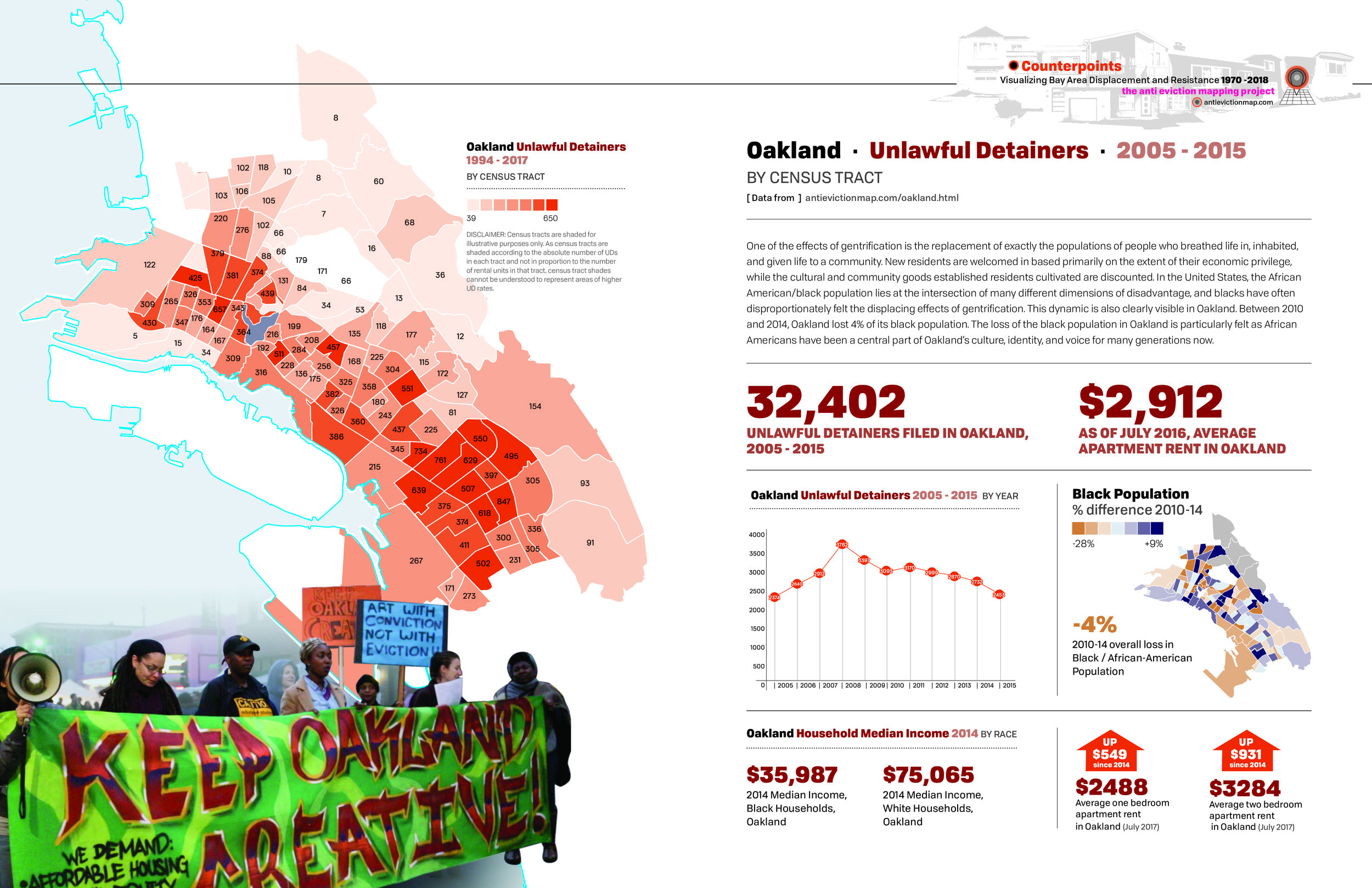

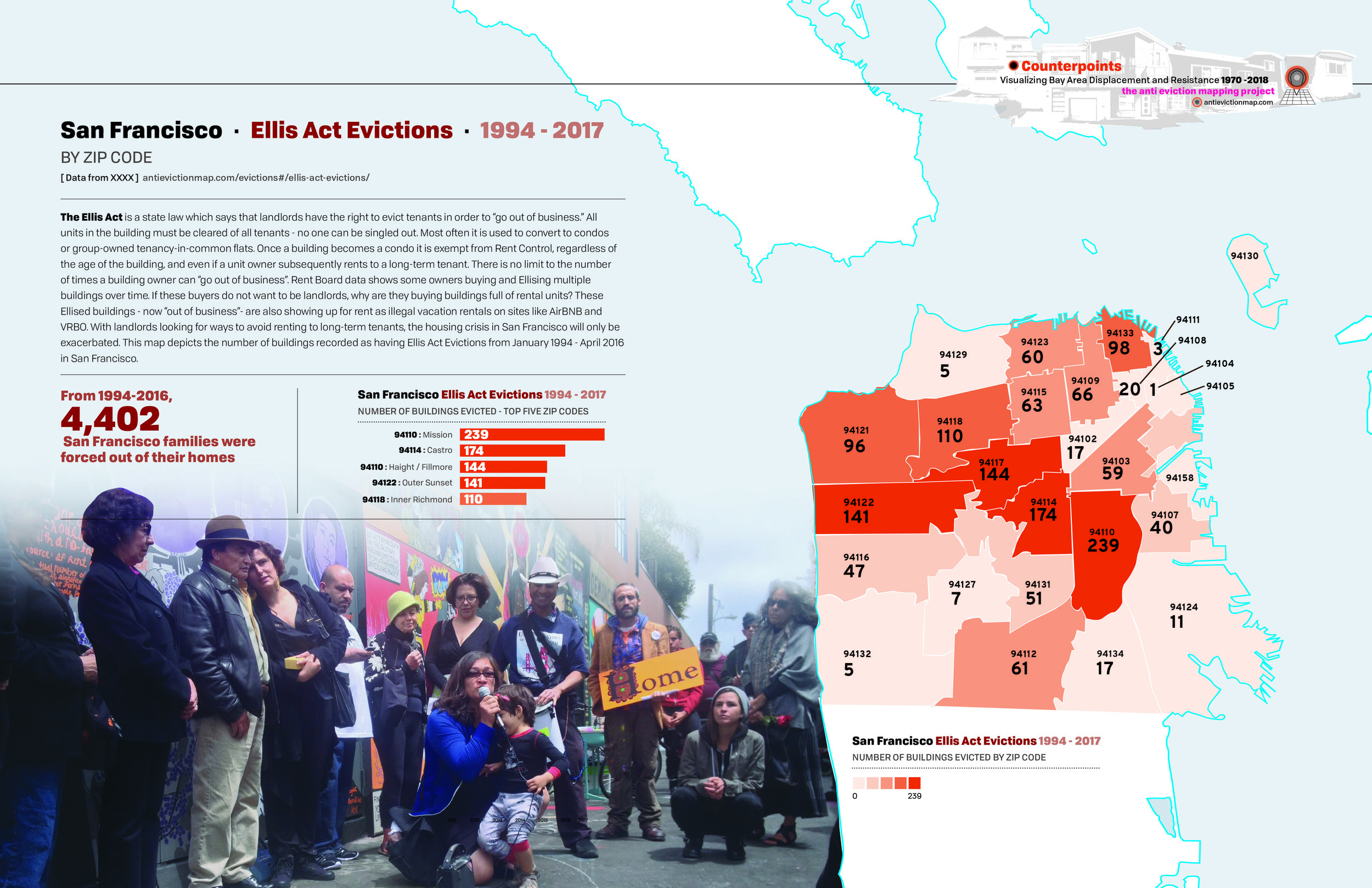

Evictions

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project emerged in 2013 in a context in which evictions were rising throughout the San Francisco Bay Area, from Oakland to San Jose, from San Mateo to San Francisco. This growth of displacement is the result of a number of factors, from the lingering effects of the foreclosure crisis to new modes of real estate speculation capitalizing on the region’s new tech boom. The contours of this new wave of displacement varies city by city, neighborhood by neighborhood, as does the data with which we map. Although the AEMP began by primarily mapping in San Francisco, since then we have grown, working alongside housing justice collectives throughout the region to map and analyze eviction data. This chapter highlights some of that work, offering an array of geographies and analysis to render one of the most devastating impacts of the contemporary gentrification crisis - forced displacement. By eviction and forced displacement, we don’t simply mean official eviction notices, although often these are our only sources of data. We recognize that frequently people are forcibly displaced without official eviction notices, due to inability to pay rent, harassment, and buy-outs, to name a few. As we have found through collaborative work, forced displacement operates at the nexus of racism, classism, sexism, ableism, ageism, and more. In addition to displaying this data geospatially, in this chapter we also look at community resistance that occurs in the direct action and policy spheres, and well as collective mural projects that help depict stories of loss but also of community power.

Colonialism and Indigenous Resistance

Though Native people have been discursively confined to rural reservations, the San Francisco Bay Area is home to Indigenous communities that have been resisting displacement for centuries. What is now known as the Bay Area spans the traditional, ancestral, stolen, and unceded territories of the Ohlone and is also home to diverse American Indian communities and Indigenous migrants from around the world. While Indigenous communities have been absented from much of the research and organizing around gentrification in urban contexts, this chapter highlights the political and cultural work of Ohlone and other American Indian leaders, from urban sacred sites protection and land reclamation, to housing, and Indigenous diasporas. Though racialized urban displacement and Indigenous land dispossession are often understood as distinct or unrelated, this chapter centers Indigenous resistance to the ongoing displacements of settler colonialism, offering new ways to conceptualize and contest urban displacement.

Speculation

This chapter welcomes work that examines contemporary practices of land and real estate speculation throughout the Bay Area. We include maps and charts that examine practices in which people buy up land and housing to speculate on its future worth. Often, future worth is imagined as higher if those living in the space can be removed, whether by foreclosure or eviction. Thus in this chapter, we include data about the foreclosure crisis as it impacted the Bay Area, as well as about practices of speculative eviction. We also look at redevelopment practices and current debates between NIMBYism and YIMBYism. What happens when developers built luxury condos in working-class neighborhoods, and what happens when the city itself sells public land to some the largest developers in the United States? In addition to asking these questions, we look at the loss of SRO housing as connected to the production of new luxury tourist housing. We also examine some of the serial evictors of the Bay Area, and imbrications of real estate and technology capitalism. Lastly, we study local processes of speculation as connected to water resources and landfills, making connections between environmental racism and development imaginaries. To address resistance, we include work on community land trusts and speculative city work that transpires outside of the nexus of real estate, city planning, and technocapitalism.

Public Health, Housing, and Environmental Racism

This chapter is seeking work that examines the ways housing instability, gentrification and displacement impact community health through chronic emotional and physiological stress, environmental and economic degradation, and other toxic exposures that disproportionately impact low income communities of color in the Bay Area.

Low income, communities of color have been marginalized to neighborhoods of last resort since colonization of the San Francisco Bay Area. Targeted by racist land grabbing and exploitative economic and environmental policies, these communities have survived by creating their own social structures, systems of support, and cultures of resilience. Sadly, it is often these historical and cultural assets that make certain neighborhoods targeted for gentrification and inequitable development. Communities of color are disproportionately impacted by degraded environments and pollution; they bear the burden of the worst health disparities and are often isolated for critical infrastructure and resources to support health. Despite this fact, public health, social, and environmental conditions in low-income, communities of color have continuously been weaponized to further displace longstanding residents, while developers and gentrifiers profit from the legacies of their residence. Displacement and gentrification work to destroy communities, disconnect families and individuals from their roots and networks of physical and mental support, and deteriorate community health and well being. A snapshot of the regional impacts of racist environmental policies, toxic exposures, and the chronic stress of being displaced, evicted, unstably housed, and houseless can be understood in these maps.

Gentrification to Prison Pipeline

Taking up the term coined by Lacino Hamilton in his Truth Out article entitled, "The Gentrification-to-Prison Pipeline," this chapter looks at policing and surveillance as tools foundational to processes of gentrification. We invite work in all forms that engages with struggles against these hierarchies of violence and force that, most often along lines of race, are continually used to make way for gentrification in the Bay Area. This could mean contributions to do with militarization, incarceration, killings by police, racist municipal enforcement, criminalization of poverty/insecurity, police and military budgets, political prisoners, community accountability, and much more. Taken in conversation with one another, contributions to this chapter seek to recognize the links between processes of criminalization, incarceration, speculation, and dispossession in Bay Area communities.

Transportation and Economy

The Bay Area vividly illustrates what Neil Smith called the “see-saw” motion of capitalism, which builds up places in some moments and supersedes them in others. Throughout its history, but especially in the 20th century, the region has seen waves of expansion into new territory through the suburbanization of workplaces and housing. At the same time, efforts to refocus development are on the increase since the 1970s, particularly with the rise of the Smart Growth framework. Transportation infrastructure is key to both of these processes, and the uneven development of mobility is a fundamental aspect of inequality in the region. This section explores the links between transportation, investment, and inequality.

Possible Atlas entries include:

Infrastructure built, proposed, and unbuilt (including 1956 BART map)

Race, class, and mobility (access + capacity)

Major job clusters over 20th century

Supercommuting and “micro-commuting”

Mobility pricing

Silicon valley buses

Migration/Relocation

What happens after displacement? Where do people move, how are their relocation decisions constrained, and what regional patterns are emerging? The housing crisis is not only radically restructuring core, Bay Area cities, but also producing new housing, economic, and community dynamics in the suburban and rural periphery. Contributions to this chapter focus on displacement as a relational process to analyze how people, capital, and power flow at a regional level. This can mean studying localities outside of the traditional nine county, Bay Area designation, studying housing and migratory dynamics at a regional or subregional (e.g. North Bay, South Bay, East Bay or Peninsula focus) level, or tracing a particular process that links multiple spaces at a supra-municipal level.

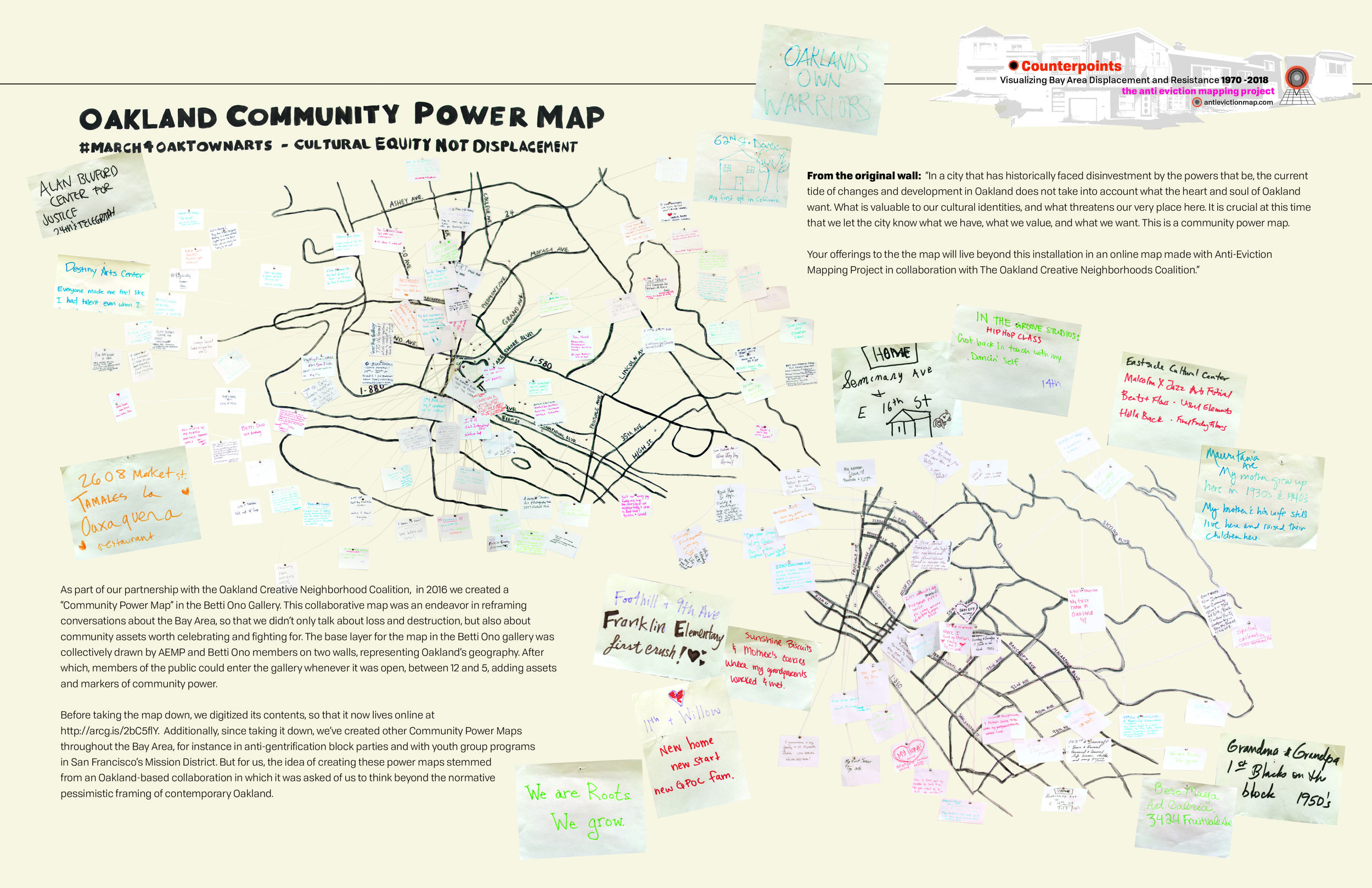

Resistance

The Resistance subsections will take the issue of each section and frame it through the specific work of an organization that focuses on the section’s topic. By working with the project or organization itself, it will bring in their expert knowledge to help inform the other writing and maps of each chapter, and give more nuance to the information and ideas of the section. By providing these secondary connections, it helps flesh out the explanation of the issues within the section, while also helping show the solutions and tactics and practices of resistance to the struggle at hand. By highlighting a certain mode of resistance to the problems of the section, it also will help to further show the ways people can mobilise to contest them.

Oral History

Throughout the chapters we will be interspersing selections from oral histories that have been collected through AEMP’s “Narratives of Displacement: Oral History Project” as well stories solicited through the Call for Papers. By collecting oral histories and presenting them as part of each chapter of the Atlas the project’s political economic and cartographic interventions will be accompanied by deep and detailed personal histories and experiences of these political economic trends and structures. In doing so the project also is a living archive of people and places as well as a counter-narrative to dominant archives that elide detail and attention to legacy, culture and loss in the Bay Area.

Policy

The Policy subsection is designed to highlight the issues in each chapter within the context of historical legislation. This subsection will build on material discussed in each chapter to expand on how the effects of a legislation and resulting actions taken by the public may have exacerbated or resolved a contentious issue. The subsection will also touch on policy recommendations the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project and its allies have introduced in previous publications.

The cover of our Atlas!